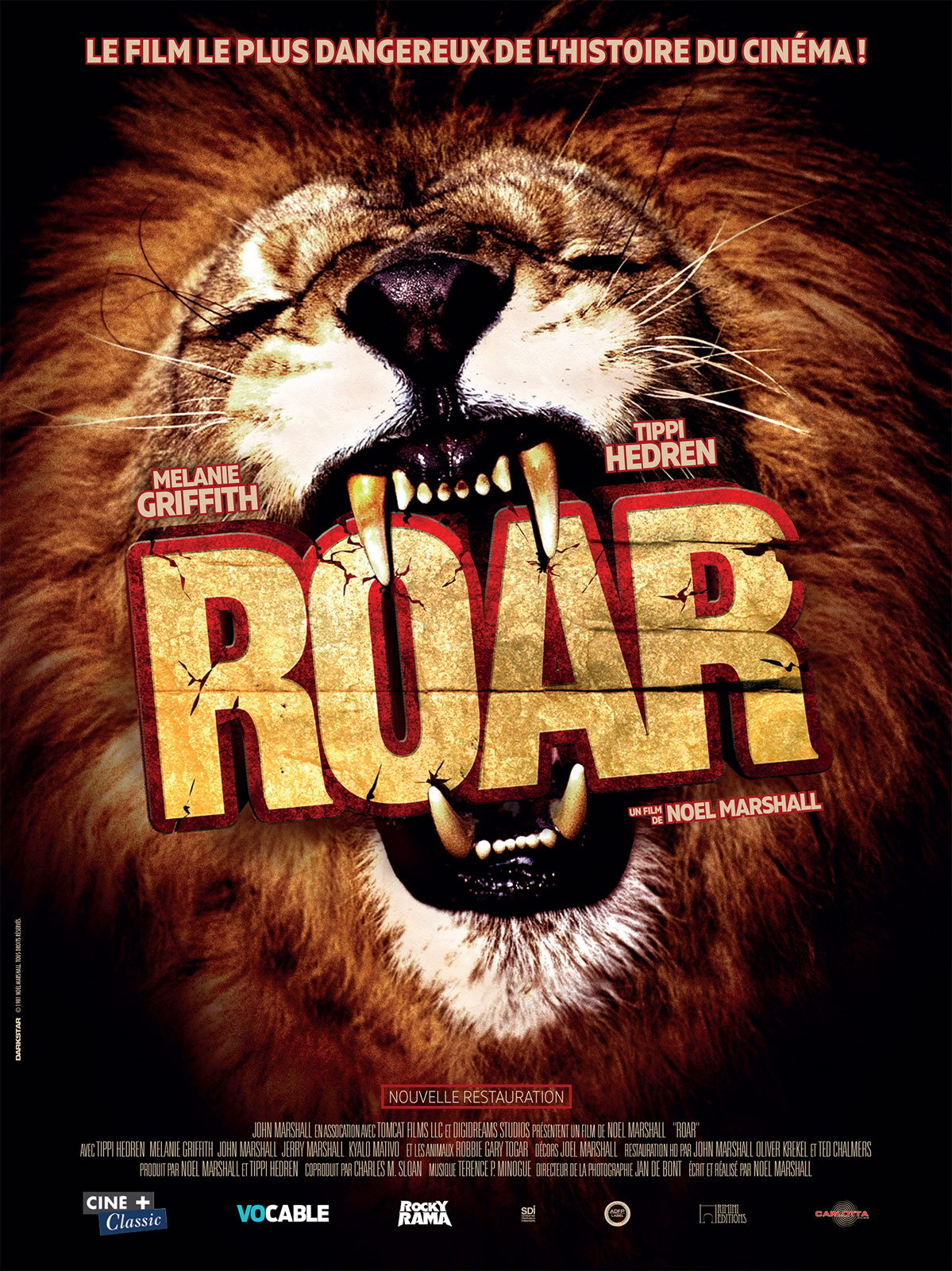

For decades, the name "Roar" has echoed through the annals of Hollywood, not just as a film title, but as a legend—a cautionary tale of ambition, danger, and the raw, untamed power of nature. The Roar movie 1981 is an American adventure comedy film unlike any other, a cinematic endeavor so audacious and fraught with peril that its very existence seems miraculous. It wasn't merely a movie about wild animals; it was a movie made *with* them, starring a real-life family who lived amongst the very creatures that became their co-stars and, at times, their greatest threat.

Written, produced, and directed by Noel Marshall, the film is a testament to an extraordinary vision, albeit one that came at an immense personal and physical cost to almost everyone involved. Its plot follows Hank, a naturalist who has forged an unconventional life on a nature preserve in Africa, sharing his home with an astonishing array of big cats—lions, tigers, leopards, cheetahs, and even pumas. The premise seems idyllic: a family reunion, as Hank expects a visit from his wife and children from Chicago. However, this heartwarming premise quickly unravels into a terrifying ordeal when the family arrives, only to be confronted not by Hank, but by the overwhelming, unpredictable presence of the very animals he calls his family.

Table of Contents

- The Unprecedented Vision Behind Roar (1981)

- The Marshall-Hedren Family: A Daring Artistic Endeavor

- The Plot of Roar: A Naturalist's Perilous Reunion

- A Production Like No Other: The Dangers of Roar (1981)

- Roar's Legacy: A Cult Classic and Cautionary Tale

- Where to Watch Roar (1981) Today

- Beyond the Roar: Animal Welfare and Conservation

The Unprecedented Vision Behind Roar (1981)

Noel Marshall, an American producer and director, harbored a dream that transcended conventional filmmaking. He envisioned a movie that would authentically portray the lives of big cats, not through special effects or trained circus animals, but by living alongside them and allowing their natural behaviors to dictate the narrative. This audacious concept gave birth to the Roar movie 1981. Marshall’s inspiration stemmed from his wife, Tippi Hedren, who, during a film shoot in Africa, witnessed a dilapidated house inhabited by a pride of lions. This encounter sparked a deep fascination and a desire to create a film that would highlight the beauty and majesty of these creatures, while also raising awareness about their plight in the wild.

The vision for Roar was simple in its ambition but revolutionary in its execution: capture the raw, unscripted interactions between humans and dozens of untamed big cats. This meant building a nature preserve in Africa (specifically, the property in California that would become Shambala Preserve, standing in for Africa in the film), acquiring and raising the animals themselves, and then filming with them in their natural habitat. The commitment was absolute, blurring the lines between filmmaking and a new way of life. Marshall and Hedren truly believed that by immersing themselves fully in this environment, they could create a film of unparalleled authenticity. This profound dedication, however, also laid the groundwork for the extraordinary challenges and dangers that would define the production of Roar.

The Marshall-Hedren Family: A Daring Artistic Endeavor

At the heart of the Roar movie 1981 was a real family, whose personal lives became inextricably linked with the film's perilous production. Noel Marshall, Tippi Hedren, and Hedren's daughter, Melanie Griffith, along with Marshall's sons, John and Jerry Marshall, formed the core human cast. Their decision to live among and act alongside dozens of powerful, unpredictable animals was not merely a professional choice; it was a profound personal commitment, driven by a shared passion for wildlife and an unwavering belief in Noel Marshall's vision. This familial bond, while providing an emotional anchor for the film, also amplified the stakes, as every injury and every close call affected not just colleagues, but loved ones.

The family's involvement lent an undeniable authenticity to the on-screen interactions, as their genuine comfort (and sometimes terror) around the animals was palpable. This was not actors pretending to be scared; it was real fear, real connection, and real danger. The film became a living document of their extraordinary, often terrifying, daily lives. Their willingness to put themselves in such vulnerable positions for the sake of art and advocacy is a defining characteristic of Roar, setting it apart from virtually any other film ever made.

Noel Marshall: The Man Who Lived with Lions

Noel Marshall was more than just the writer, producer, and director of Roar; he was its driving force, its central character, and its ultimate sacrifice. His portrayal of Hank, the naturalist living with big cats, was less an acting performance and more a reflection of his own life during the film's protracted production. Marshall's commitment to his vision was absolute, bordering on obsession. He spent years living on the property that housed the animals, observing their behaviors, and attempting to integrate them into the filmmaking process. His philosophy was that the animals were not to be merely props but active participants, and their natural instincts were to be respected, even when those instincts led to chaos.

Marshall’s dedication was unwavering, even in the face of mounting injuries and financial ruin. He poured his own money, and that of his family, into the project, believing that the unique bond he was forging with the animals would result in a cinematic masterpiece. His willingness to physically engage with the lions, tigers, and other predators, often putting himself in direct harm's way, underscored his profound belief in the film's message and his unique connection to the animals. This personal investment made Roar an extension of his very being, a raw and unfiltered look into his extraordinary life.

Tippi Hedren: From Hitchcock's Muse to Big Cat Advocate

Tippi Hedren, renowned for her iconic roles in Alfred Hitchcock's The Birds and Marnie, underwent a profound transformation during the making of Roar. What began as a collaborative artistic endeavor with her then-husband, Noel Marshall, evolved into a lifelong commitment to animal welfare and conservation. Hedren’s personal experience living with and being injured by the big cats during the film's production solidified her resolve to protect these magnificent creatures. She became a fierce advocate against the private ownership of exotic animals, recognizing the inherent dangers and the suffering it often entails for the animals themselves.

Following the tumultuous production of Roar, Hedren established the Shambala Preserve, a sanctuary for exotic felines that have been rescued from abusive or neglectful situations. Her work at Shambala, which continues to this day, directly reflects the lessons learned from Roar. She understood firsthand the immense power and unpredictability of big cats, and her advocacy became focused on ensuring that no other individual or family would have to endure the risks she and her family faced. Hedren’s journey from Hollywood starlet to tireless animal rights activist is a powerful testament to the enduring impact of the Roar movie 1981 on her life and the broader conversation about human-animal interaction.

The Plot of Roar: A Naturalist's Perilous Reunion

The narrative of the Roar movie 1981, while seemingly straightforward, serves primarily as a framework for the extraordinary animal interactions that dominate the screen. The story follows Hank, a naturalist who has made an astonishing life for himself on a nature preserve in Africa. His companions are not other humans, but a sprawling, diverse family of big cats: lions, tigers, leopards, cheetahs, black panthers, and even pumas. Hank's world is one of precarious balance, where he attempts to live in harmony with these powerful predators, believing he understands and can manage their wild instincts.

The central conflict arises when Hank's family—his wife and their four children from Chicago—decide to visit him in his remote African sanctuary. A naturalist living with big cats in East Africa expects a visit by his family of four from Chicago, anticipating a joyous reunion. However, their arrival takes a terrifying turn. Instead of being greeted by Hank, they are immediately confronted by the very group of animals he lives with. Hank is away, and his family, unprepared for the sheer number and unpredictable nature of the big cats, finds themselves trapped and terrorized within his home. Roar's story follows Hank, a naturalist who lives on a nature preserve in Africa with lions, tigers, and other big cats, and then plunges his unsuspecting family into a desperate struggle for survival against these magnificent, yet dangerous, creatures. The film becomes a harrowing cat-and-mouse game within the confines of Hank's house, as the family attempts to navigate the unpredictable movements and moods of dozens of wild animals, desperately trying to find Hank and escape their perilous predicament.

A Production Like No Other: The Dangers of Roar (1981)

The Roar movie 1981 is perhaps the most infamous example—a production many believe is one of the most dangerous films ever made. To this day, it serves as a potent reminder of the inherent risks involved when attempting to blend the unpredictable world of wild animals with the controlled environment of a film set. The production was dangerous and chaotic, with many cast and crew members being bitten, scratched, and scalped by the animals. This wasn't merely a few minor incidents; it was a continuous, harrowing ordeal that lasted for years, pushing the boundaries of what was considered acceptable in filmmaking.

The sheer number of animals involved was staggering: between three and forty-five lions at any given time, a dozen tigers, several leopards, cheetahs, black panthers, and even pumas. These were not docile, highly trained animals; they were largely wild, and their interactions with the human cast and crew were unscripted and often violent. The dedication to authenticity meant foregoing traditional safety measures, leading to a production history filled with astonishing tales of injuries and close calls that have become legendary in Hollywood lore. The film's unique, almost documentary-like feel of genuine peril is a direct result of this unprecedented and terrifying production methodology.

Injuries and Close Calls: The Unscripted Reality

The stories of injuries sustained during the filming of the Roar movie 1981 are legendary, painting a vivid picture of the extreme risks taken. While the film proudly states "No animals were harmed in the making of this movie," the same cannot be said for the human participants. A staggering 70 members of the cast and crew were injured, a number that speaks volumes about the constant peril on set. These weren't just minor scratches; many were severe, life-threatening incidents.

One of the most widely cited incidents involved cinematographer Jan de Bont, who would later become a renowned director himself (Speed, Twister). De Bont was mauled by a lion on the set, an attack so severe that over 120 stitches were needed to sew his scalp back in place. Incredibly, after medical treatment, De Bont returned to the production to complete his director of photography duties, a testament to the crew's extraordinary commitment, or perhaps, their sheer stubbornness in the face of danger. Melanie Griffith, then a teenager in her first major film role, was also severely injured, requiring facial reconstructive surgery after a lion attack. Tippi Hedren herself suffered a fractured leg and numerous bite wounds. Noel Marshall was repeatedly bitten, contracting gangrene at one point. These incidents highlight the brutal reality of working with apex predators, where every take carried the potential for serious harm or even death. The film's chaotic and unpredictable nature on screen was a direct reflection of its real-life production.

The Ethical Dilemma: Man vs. Wild on Set

The production of the Roar movie 1981 presents a profound ethical dilemma that continues to be debated. On one hand, there was a clear intention to showcase the majesty of big cats and advocate for their conservation. The filmmakers genuinely loved these animals and believed they were creating something unique to foster understanding. On the other hand, the methods employed led to an unprecedented number of human injuries, raising serious questions about the responsibility of filmmakers towards their cast and crew, and the ethical boundaries of artistic pursuit.

The philosophy that allowed "between three and forty-five animals, a dozen tigers, several leopards, cheetahs, black panthers, here and there even pumas" to interact freely and unscripted with actors, including a teenage Melanie Griffith, pushed the limits of safety and common sense. While the claim "No animals were harmed in the making of this movie" stands, the inverse is strikingly true for the human participants. This stark contrast forces viewers to confront the cost of authenticity. Was the unique footage worth the physical and psychological trauma inflicted upon the cast and crew? Roar serves as a powerful, if uncomfortable, case study in the ethical considerations of filmmaking, particularly when working with dangerous elements, and remains a touchstone for discussions on animal welfare in entertainment.

Roar's Legacy: A Cult Classic and Cautionary Tale

Despite its tumultuous production and initial struggles to find distribution, the Roar movie 1981 has carved out a unique and undeniable legacy in cinematic history. It stands as a cult classic, celebrated not just for its thrilling adventure elements, but more so for the incredible, unscripted animal interactions and the sheer audacity of its making. It’s a film that demands attention, precisely because of the stories behind its creation. For many, watching Roar isn't just about following the plot; it's about witnessing real danger unfold, knowing the human cost involved in every frame.

Beyond its cult status, Roar functions as a potent cautionary tale. It serves as a stark reminder of the inherent dangers of attempting to control nature, especially when dealing with powerful, wild animals. It highlights the fine line between artistic vision and reckless endangerment, sparking ongoing conversations about safety protocols in filmmaking and the ethical treatment of both humans and animals on set. Its enduring relevance lies in its ability to shock, fascinate, and provoke thought, ensuring that the legend of Noel Marshall's wild experiment continues to be discussed and debated for generations to come.

Where to Watch Roar (1981) Today

For those intrigued by the legendary production and unique cinematic experience of the Roar movie 1981, the good news is that this infamous film is more accessible than ever. Despite its limited initial release, Roar has found a new audience in the digital age, allowing viewers to witness its breathtaking wildlife scenes and extraordinary story from the comfort of their homes. If you're looking to watch the thrilling adventure film Roar (1981), there are several options available.

One of the most convenient ways to immerse yourself in this movie's story anytime is to watch it for free on The Roku Channel. This provides an excellent opportunity for a wide audience to discover this truly unique piece of cinema. Additionally, you can discover streaming options, rental services, and purchase links for this movie on Moviefone, which aggregates various platforms where the film might be available. While the data mentions "Stream 'Roar (2015)' and watch online," it's important to clarify that the film in question is the original 1981 release, which has seen re-releases and digital availability in recent years. So, whether you're looking to stream, rent, or purchase, experiencing the bonkers #roar is now easier than ever, offering a glimpse into one of Hollywood's most audacious and dangerous productions.

Beyond the Roar: Animal Welfare and Conservation

The legacy of the Roar movie 1981 extends far beyond its cinematic impact and production notoriety. It inadvertently became a catalyst for significant advancements in animal welfare and conservation, largely due to the tireless efforts of Tippi Hedren. The film's chaotic and dangerous production, which saw humans and wild animals interacting with minimal safety barriers, underscored the profound risks associated with the private ownership and commercial exploitation of big cats.

In the wake of Roar, Tippi Hedren dedicated her life to advocating for the humane treatment of exotic animals. Her establishment of the Shambala Preserve serves as a direct response to the lessons learned on set, providing a safe haven for rescued big cats and actively campaigning for legislation that restricts private ownership and regulates animal entertainment. The film, therefore, serves as a powerful, albeit unintended, educational tool, highlighting the inherent wildness of these animals and the ethical imperative to protect them in appropriate environments. It reminds us that while the allure of interacting with magnificent predators is strong, their true welfare and conservation lie in respecting their wild nature and ensuring their survival in natural habitats or accredited sanctuaries, rather than in potentially dangerous and exploitative human-controlled settings.

Conclusion

The Roar movie 1981 remains a singular phenomenon in film history—a testament to an unparalleled vision, an extraordinary commitment, and a production fraught with unimaginable peril. It is a film that defies easy categorization, blending adventure, comedy, and sheer terror into a narrative that is as captivating as it is concerning. From Noel Marshall's audacious dream to Tippi Hedren's enduring legacy in animal welfare, Roar is more than just a movie; it's a chapter in the history of human-animal interaction, a cautionary tale of ambition, and a raw, unfiltered glimpse into the untamed world of big cats.

Its infamous production history, marked by dozens of injuries and years of dedicated effort, ensures its place as one of the most talked-about and dangerous films ever made. Yet, it also sparked crucial conversations about ethical filmmaking and the responsible care of exotic animals. If you haven't seen it, watching Roar (1981) is an experience unlike any other, a visceral journey that will leave you questioning the boundaries of cinema and the wild heart of nature. We encourage you to seek out this unique film and share your thoughts in the comments below. Have you seen Roar? What did you think of its legendary production?